Filmmaker George Colburn’s relationship with Dwight D. Eisenhower has endured more than 30 years

In the summer of 1988, documentary filmmaker George Colburn agreed reluctantly to take a meeting in Washington, D.C. with three former aides of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The surprise invitation included a vague mention of a discussion of the legacy of our nation’s 34th president.

Colburn slightly knew only one of the three men, Abbott Washburn, an FCC Commissioner who was a friend of a friend in New York City where Colburn’s media and education business had been located for the previous eight years. When he arrived at Commissioner Washburn’s office, Colburn was not aware that in just over two years, it would be time to commemorate “Ike” and his legacy during the observation of Eisenhower’s 100th birthday, October 14.

But Colburn was about to move his small media and distance education business from New York City to Los Angeles. Before doing so, his “to do” list was long. He had to pack up his mid-town office and his upper east side apartment and move everything back to his personal home base in the northwest corner of Michigan’s lower peninsula.

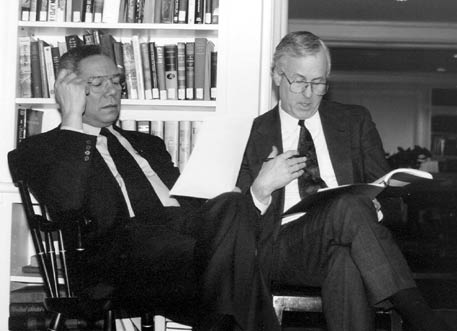

Dr. George A. Colburn interviews former President Richard M. Nixon in 1991 for the first program in The Eisenhower Legacy series.

His daughters would soon show up there for their annual summer holidays. And then there was the long drive ahead to southern California and getting settled ASAP somewhere in the L.A. area. A new project he was to direct was already underway without his presence. “True chaos” is how he remembers the day when he received the call from Washburn.

Several years earlier, at the request of a friend who knew Colburn, Washburn had made a call to the famous futurist author Arthur C. Clarke at his home in the island nation of Sri Lanka. Colburn and others were developing a series about “the communications revolution” that could use a boost from Clarke’s expert commentary on the subject. Thanks to Washburn’s call, Clarke welcomed Colburn and his crew to Sri Lanka shortly thereafter and provided them with his thoughts on-camera about the future of communications.

By the end of the telephone conversation with Washburn, Colburn realized it was his time to repay the “debt” he had incurred a few years earlier. “When I got the picture,” Colburn said, “I immediately accepted the invitation to come to Washington and talk about the Eisenhower presidency.”

But, on that hot and humid summer’s day in the nation’s capital, Colburn thought his visit would include a short courtesy call on Washburn and friends. And that at the end he would politely say, “thanks, but no thanks.”

Instead, it ended up being a life – and career – changing day.

Washburn, a World War II intelligence officer in Europe, had been Ike’s #2 person at the Voice of America during the two-term Eisenhower administration in the 1950s and before that, he was a major player in the campaign that got Ike elected President. At the meeting were two others who had also played key roles during Ike’s White House years. Gen. Andrew Goodpaster, a World War II infantry officer, had been, in effect, Ike’s senior national security aide during most of the two administrations. William Ewald, who held a Harvard University Ph.D. in literature, had been an Eisenhower speech writer for several years after working as a volunteer in the 1952 election.

Ewald had written two important books in recent years about the Eisenhower presidency, but Colburn, a historian, was not aware of them. The film producer admitted that he had thought little about “Ike” in the years prior to that fateful meeting with Washburn and his colleagues. But at that gathering, the three aides gave Colburn plenty to think about. “It was like fresh meat to a historian,” Colburn said.

“Like many others I had always thought of Eisenhower as an important General of the Army in World War II – “the man who beat Hitler.” In Colburn’s mind, Ike was a war hero to most Americans and, as a result, got himself elected president a few years later. But, in the White House, “he didn’t do much as far as I knew.”

Colburn has a Ph.D. in history from Michigan State University and taught American Studies there for four years while writing his dissertation about Anglo-Irish politics of the 1880s. But, he says President Eisenhower’s presence on the world stage for 20 years and his important roles in major military and foreign policy decision-making never crossed his mind while pursuing his graduate studies at MSU in the 1960s.

“It was Kennedy and Johnson and Nixon then,” he notes, “and Ike was like ancient history to those of us who weren’t old enough to vote in the 1950s.” During his graduate studies, Colburn accepted the consensus view of most historians that Ike was pretty much a “do nothing” President. “He was a grandfather who liked golf,” was the view from the Colburn clan growing up in a new working-class neighborhood of “cookie cutter” homes on Detroit’s far west side.

“Besides, we children of Detroit’s factory workers were busy in the 1960s with our own important business then, and for me it included fighting for civil rights and against the war in Vietnam,” Colburn added. But the “history lesson” Colburn was offered over a couple hours by Washburn, Goodpaster and Ewald, prompted him to accept their challenge “to do a little digging” on the subject of the Eisenhower presidency.

“You won’t have to look hard,” they assured him. And they said he would surely be surprised.

He did. And he was.

It was revisionist history in the making, and Colburn had written a revisionist dissertation about a major Irish politician in the British parliament who got “short-changed” by historians, he says. And that taught him a lot about the field of history and the shortcomings of historians with their own personal agendas.

Once convinced that Ike would be a good subject for a “breakthrough” television documentary, his next step was to find the financing for such a program that would present the Eisenhower legacy in the light of new research then coming out in articles and books. But few people “in the biz” were convinced that “Ike” as president was a story worth telling.

Colburn’s experience as a filmmaker was limited at that time, but he had “kept his eyes open” while raising money for national media education projects at the University of California, San Diego, in the 1970s and for his own projects while operating out of New York City in the 1980s.

He had followed closely the work of BBC-trained producers and directors who crossed paths with him while working on productions in the U.S. He got to know many of them who were on the lookout for jobs outside the BBC. He signed up one of these BBC alums who had re-settled in California to be the director for his Eisenhower documentary. Colburn would do the research, interview the “witnesses to history” that Washburn had promised to find him, and then create the story line based on what his witnesses had told him.

It took Colburn almost three years to get that first program on the air. Entitled “Dangerous Years,” the documentary on President Eisenhower’s Cold War foreign policy first aired on the Discovery Channel in the fall of 1991 – more than a year after the Centenary commemoration had taken place.

But the one-hour program (only 45 minutes if you consider the commercials) was loaded with important commentators like Vice-President Richard Nixon, key CIA and State Department officials, Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Pentagon scientists, ICBM experts and important officials from the French, British and German governments. They were found and rounded up for interviewing by Abbott Washburn, “the man with the largest Rolodex in Washington,” according to Colburn.

Producer George Colburn works with Colin Powell on the host’s script for The Eisenhower Legacy series that premiered on the Disney Channel in 1998.

With the help of Maxwell Rabb, another Ike aide who was an ambassador in the Reagan administration, Colburn and a film crew even managed in late 1990 to attend a week-long Eisenhower Centenary conference in Moscow. As the Soviet Union began to fall apart, Colburn was able to interview Nikita Khrushchev’s son-in-law, editor in the 50s of Izvestia, the official USSR newspaper, Khrushchev’s foreign minister, and the head of the Soviet Space Institute.

By this time, the Eisenhower story line had hooked Colburn. It was a story line that was largely unknown to the average American and unacceptable to most historians who, Colburn believes, were still awed by the lost promise of the late President Kennedy who had followed Ike into the White House. “The Eisenhower Myth” was what Washburn and other Eisenhower supporters called the deeply engrained negativity about Ike’s presidency that was a holdover from the JFK campaign versus Richard Nixon, Ike’s Vice-President.

“It was a great story,” Colburn said and, so, to keep up his research and his interviewing about Kennedy’s predecessor, Colburn walked away from his project in L.A. and moved in 1992 to Washington, D.C. He and his wife Karen left L.A. the day after his first film on Ike aired nationally in prime time on Discovery. “All of our friends were in our living room to watch it with us, and it was the perfect send-off,” Colburn recalls.

By 1993, he had found the funding (again with Abbott Washburn’s help) to produce “Contentious Years,” a documentary on President Eisenhower’s domestic policies, especially his “hidden hand” strategies that would destroy Sen. Joe McCarthy’s political power and convince the Congress to pass the first civil rights legislation since Reconstruction.

The two Eisenhower specials did not generate large numbers on Discovery, but they were noticed in the right places. From the Disney Channel came a call for Colburn to produce a D-Day documentary for the 50th anniversary in1994, a show that would focus on Ike’s military leadership in World War II. But, during post-production, Colburn suffered a heart attack and the documentary became a “V-E Day Plus 50 Years” special a year later.

All three of these early documentaries were hosted and narrated by legendary NBC News anchor John Chancellor, himself a witness to the history of the Eisenhower years and a great admirer of President Eisenhower whom he covered as a young reporter. The experience with Chancellor – and the newsman’s enthusiastic support for the productions – gave Colburn the confidence to continue with his storytelling about Ike and his era.

“When Karen, and I took John the final edit for my first Eisenhower program -‘Dangerous Years’ – to his summer getaway on Nantucket in early September of 1991, I had no idea what to expect,” Colburn notes, “but his comments afterwards prompted all of us, perhaps, to drink one or more too many G&Ts to the on-air success of the program.”

Chancellor went public in 1993 regarding Colburn’s filmmaking skills when he spoke before The Eisenhower Institute, the organization with a mission to promote the Eisenhower legacy that prompted Washburn to approach Colburn in 1988. At the outset of his talk, Chancellor noted the attendance in the back of the hall of “that distinguished documentarian, George Colburn.” Chancellor had been on locations around Washington that day for his role as host of “Contentious Years.”

And, yes, it created quite a stir….and it is really happened. Colburn has a VHS cassette from C-Span of Chancellor’s remarks, prompting a former student to write a song entitled “The Distinguished Documentarian.” And, yes, he has a DVD of the student performing the song on the deck of his Michigan home.

The “long march” with Ike now began in earnest.

Colburn was then asked by Disney to produce a follow-up up to his V-E Special by creating a four-part series on Eisenhower that would cover the complete story of his public life from 1941 to 1961. But Chancellor had serious medical issues and could not host the shows. Another highly visible host, Gen. Colin Powell (USA, Ret.), signed on to be the “face” of the series.

“Yes, again, it was thanks to Abbott Washburn, “the godfather of the series,” Colburn emphatically reminds people. Gen. Powell was known to most Americans at that time, and many wanted him to run for President. But, Powell did not know the revisionists’ story of the Eisenhower Presidency, and it led to last-minute script changes for the host’s remarks on-camera.

The four-part series entitled “The Eisenhower Legacy” first aired on Disney in 1997. A few years later, the series also appeared on the History Channel and reached millions more in prime time.

Also, in 1997, Colburn wrote and produced a 20-part classroom series (approximately 10 hours of programming) about “The Eisenhower Era, 1941 – 1961,” for Disney Educational Productions. This series, edited in Los Angeles, was the end of Colburn’s “long march” with Ike. “It had been a decade since I started my research about the Eisenhower presidency,” Colburn says, “and I decided to give myself a ‘sabbatical’ and retreat to our vacation home in a remote corner of Michigan.” With seven nationally broadcast programs and 20 educational programs behind him, Colburn believed he was now able to lie low for a while and figure out what to do next.

That sabbatical year turned into a second year when he was attracted to some Michigan-based documentary projects – and a major rebuilding project at his home. In addition, with the internet now available even in a rural area like Walloon Lake, Michigan, plus the arrival of regional jets at an airport 50 miles away, the Colburns decided in 1999 to leave the urban life behind them for good.

But, Ike would not leave him alone for long. In 2002, on the 50th anniversary of Ike’s first election as President, Colburn attended the commemoration in Abilene and met for the first time several key officials of the grassroots “Citizens for Eisenhower” organization that helped Ike win the GOP nomination and then the presidency. These officials – all ex-servicemen – convinced Colburn that the story of the 1952 election had been largely ignored by the history books and was worthy of more consideration, especially on television.

The really big question for them was, says Colburn: “What if Robert Taft, a neo-isolationist U.S. Senator, had been nominated as the Republican candidate in 1952?” This was the constant question Colburn got from Stanley Rumbough, co-founder of Citizens for Eisenhower: The Rumbough reply: “Taft would have beaten the Democratic nominee and then as President he would have withdrawn all support for our Allies in Western Europe who would then have to face the Soviet Union on their own.”

Rumbough would say it over and over again, “Ike saved the world.” This was a common remark by those who worked for Eisenhower’s election in 1952 and again in 1956 after fighting for him in World War II.

Over the next several years, Colburn conducted interviews and then worked up a treatment about the Eisenhower presidency that showed how hard Ike had to work to win the election. The new program considered three questions: “why he ran, how he won and why it mattered.” His two-hour documentary, “Eisenhower’s Secret War,” answered these questions, but it was many years later before it would air nationally on public television.

Finding funding was the ongoing problem. Ike was still not a name that drew viewers, or so program distributors claimed as Colburn made the rounds. With money found here and there, and from his own company, the documentary was finally finished and then distributed in 2012 to public television stations across the country. And, yes, his company paid distribution costs to get it on-air. Almost all the stations across the country carried the two hours, and it was repeated many times over a five-year period.

In Part One, “The Lure of the Presidency,” Ike’s tortured decision-making prior to nomination is considered as well as his difficult campaign, first of all in the primary against U.S. Senator Robert Taft, the conservative “Mr. Republican,” and then against Democratic Governor Adlai Stevenson in the general election.

Ike’s campaign benefited greatly from his experienced “Madison Avenue volunteers” who knew the importance of those new television sets in American homes, and how to use the “I Like Ike” slogan effectively in that new medium. The opposite was true in the Taft and Stevenson camps. The Eisenhower campaign thus became the first in presidential politics to take full advantage of this new communications technology.

Part Two of the documentary is entitled “From Warrior to President,” and it focuses on why it mattered that Ike was in the Oval Office rather than a politician with scant knowledge of military strategy, rockets, nuclear weapons and the Pentagon budget. “Nuclear war was avoided in this early phase of the Cold War,” Colburn says, “and nothing else really mattered to the general public in that uncertain time only a few years after the end of World War II.”

By “covertly waging peace” throughout the post-war era Eisenhower was steady in his leadership of the U.S. and “the free world,” Colburn notes; “an incredibly important fact that has helped Ike attain the high ranking he now has among historians and political scientists.”

Colburn has concluded that “There was no one else on the political radar who could have kept Cold War tensions under control despite major setbacks like the Sputnik space launch by the Soviet Union and our U-2 spy plane crash over the USSR early in his 2nd term. “The American people trusted him despite those disasters,” Colburn notes, “and he was able to keep open the pathway to peaceful co-existence with the communist world.”

The late John Chancellor (right) hosted and narrated the first three Eisenhower Legacy specials. At West Point, Colburn directs cameraman Vince Gancie as Chancellor waits for his cue.

Since Colburn first went into production in 1990 during Eisenhower Centenary conferences in Abilene, Kansas; Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; and Moscow, USSR, in October 1990, he has interviewed approximately 160 “witnesses to history.” The list includes four former U.S. presidents, key White House staffers, CIA officials, former members of Congress, journalists, ICBM scientists, key members of foreign governments and leading authors and scholars who have carried out breakthrough research about the Eisenhower legacy in recent years. He is especially proud of the fact that the scholars seem to like his programs. “If you want to know Eisenhower, you have to know Colburn’s films” is how distinguished Professor H.W. Brands at the University of Texas put it a few years ago.

Colburn says he learned from these interviews that Eisenhower “was supremely secure in himself. He had no reason for self-promotion after his World War II exploits. His war experience – and the weapons of modern warfare introduced on the World War II battlefields – prompted him to become totally committed to peace.” His Farewell Address, according to Colburn, is revealing because of his obvious disappointment on camera when he paused and admitted that his quest for peace was not a complete victory.

Now, his “hidden-hand” tactics as President are well-known in the scholarly world, if not by the general public, according to Colburn. “In many instances, these tactics were vital to Ike’s success; the general public could not know exactly what he was thinking or willing to do,” Colburn said. “We see this playing out in the second hour of Eisenhower’s Secret War.”

Eisenhower’s image has been helped greatly by the ongoing opening of his papers in Abilene over the past three decades and the scholarly books that followed. “The Eisenhower Papers in Abilene have provided scholars and writers in recent years with a clear view of Ike’s strategies and the subsequent actions that helped implement the strategies,” he said. “They clearly show Ike to be a man with a plan – a plan to keep the peace, not to win the peace except by our example.”

“He was a totally confident Commander-in-Chief who made one critical decision after another in the interest of keeping the peace,” Colburn added. “Major setbacks like the Soviet space launches only made him more determined to keep on the path of peace. “There was no ‘saber rattling’ after Sputnik,” Colburn says, “only a calm message that the U.S. was not threatened by the satellite and that the U.S. would keep on a peaceful path to explore our options in space.”

The latest scholarship on Eisenhower has resulted in most experts now ranking Eisenhower among the handful of greatest presidents in U.S. history – an amazing ascent from the rankings in 1988 when Colburn started his exploration of the Eisenhower legacy. Ike was ranked in the 22nd spot in the 1980, but today as his Memorial on the National Mall is completed, he is ranked as high as 5th in a C-Span survey in 2017.

Only Washington, Lincoln and the two Roosevelts outrank him. “Finally, he is where he should be,” Colburn says. “These accolades were a long time coming, well deserved, but still hard to believe that I have been a participant in the long march with a vastly underrated President to one who rates a place alongside the giants of American history.”

Colburn says he chuckled to himself when the late Republican Senator Ted Stevens from Alaska told him early in the research phase of “Dangerous Years” that Ike was “the most important President of the 20th century.” By the time Senator Stevens and his Democratic colleague, Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii, kicked off their campaign for an Eisenhower Memorial in the 1990s, Colburn was no longer chuckling; he knew better by then.

Today, Colburn is in the final stage of a 10th documentary on Eisenhower that will premiere for a private audience the evening before the dedication of the Memorial on September 17. Entitled Ike, 1941 – 1945: The Making of an American Hero, the program examines the tough decisions that Ike made on the battlefield – and behind the scenes – and why it mattered to the world in the 1950s that Ike was “The Man Who Beat Hitler” on the killing grounds of western Europe in 1944 – 1945.